By Sonya Ben Yahmed

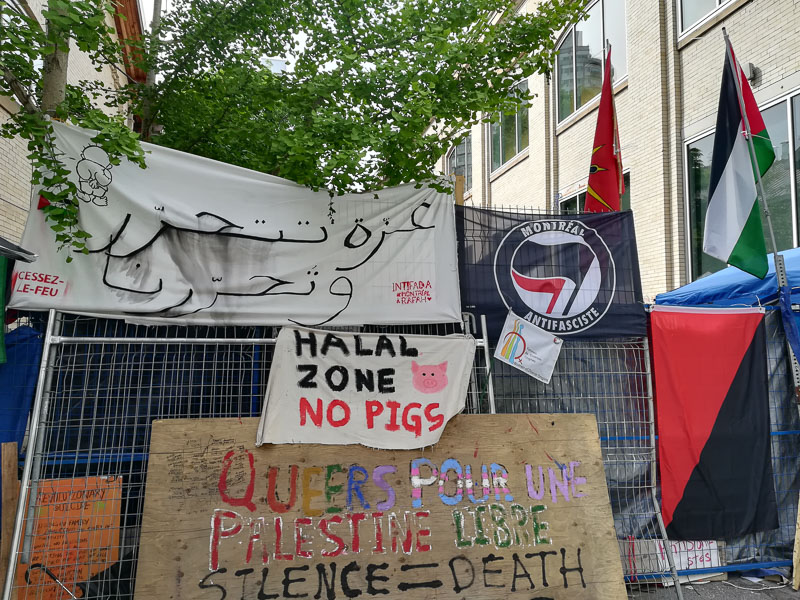

This text is written in resonance with a communication presented during a counter-event of the Congress of the Federation of Human Sciences (FHS), in June 2024, in Montreal. The counter-event was organized to protest the FHS’s lack of position on the genocide in Gaza and the pro-Palestinian student movement, as reflected in the encampment at McGill University where the congress was supposed to take place.

In this text, I take a brief inventory of the pro-Palestine mobilization in Canada and the recent backlash. I argue for the importance of a militant ethnographic approach (Juris, 2007) in this context, that mobilizes participant observation and autoethnography (Ellis and al., 2011), in connection with my involvement and a regular and diligent participation to the Al Aqsa Popular University (APU) student encampment, at the Université de Québec à Montréal (UQAM).

The experience of the encampment is very rich and deserves to be reported in a way that accounts for it. For my part, I deal here with specific elements, notably in relation to the educational alternative that the APU could represent and the question of violence.

We will see that a paradigm shift has become possible, by placing, more than ever, resistance at the heart of the struggle and by articulating it around a discourse of ongoing victory.

Struggle for Palestine in Canada, pre and post October 7th

Palestinians and pro-Palestine activists have experienced, especially since October 7, 2023, great repression and “fierce attack on freedom of expression” in the West (Awres, 2023). Artists, academics, journalists, politicians, and more are censored, defamed, and fired. In different liberal democracies such as Quebec and Canada, which espouses freedom of expression as a highly defended value, various pro-Palestine events are banned or canceled (Dupuis-Déri, 2024).

This hunt mobilizes discourses and rhetoric that range from allegations of anti-Semitism, even against Arab and Jewish people, to pro-Islamism, while instrumentalizing the issue of gender and women’s rights[1] In this regard, one can for example read the statement of Women of Diverse Origins: https://www.facebook.com/share/p/xBEdRP8vanZFeEKG/

and violence. This “new anti-Semitism” aims “to dispose of the facts and evidence supporting criticisms of the Israeli state’s oppressions and crimes and to discover in their place libelous slurs against Israel that resonate with the shameful tropes of European anti-Semitism,” as Michael Keefer (2024, p.125) puts it.

Despite its alarming nature, this situation is not new. In the media world, for example, Davide Mastracci (2024) emphasized publication policies that exclude any criticism of the Zionist entity, ranging from refusing to publish to veteran journalists, dismissal, and even the rejection of content when pro-“Israel” groups put pressure on the media.[2] This goes against the principle of freedom of expression advocated and defining the very existence of many media publications. Similar groups of censors act within universities, through class action lawsuits that they file against students, professors and faculty, accusing their own institutions of not protecting students and faculty against the anti-Semitic harassment they say they suffer.

The tracking and surveillance of pro-Palestinian activists in all spheres where they are active is, obviously, not new. October 7 remains, however, a date from which the pro-Palestine mobilization has occupied more spaces and made itself visible; the same goes for backlash and repression.

Some methodological and terminological elements

My long-time activism for Palestine naturally led me to get involved in the encampments’ movement at a time of genocide in Gaza, and my activist involvement led me, as a researcher, to do a methodical observation as a part of what we can call a “militant ethnography”. This concept of activist and anthropologist Jeffrey Juris (2007) combines politically engaged participant observation and ethnography, and is premised on a high reflexive collaboration between ethnographers and activists, generally in anti-authoritarian networks. It aims to produce politically applicable knowledge from within structures and movements (Apoifis, 2016) and highlights the importance of making this knowledge accessible both to the academy and the relevant social movements.

Participation and political solidarity with their collaborators, in addition to a commitment to distribute knowledge after the research is completed, are mandatory for this kind of ethnography. Also, several reflections and implementations of mechanisms that promote the democratization of knowledge and respect for the question of representation are important here; for example, the attempt to make output accessible to activist networks and respect the agency and voice of the collaborators.

It is with this in mind that this article is written.

In the following section, I will focus particularly on the educational aspect of the encampment and two moments which seem to me to be particularly important in its history. In doing so, the content will remain deliberately general at times, especially in the part concerning violence and sense making, out of regard for security issues.

Student mobilizations: the case of the APU

In resonance with the encampments that have emerged in the United States, starting from April 2024, several have been established in different universities in Quebec and Canada to protest against the genocide and the complicity of the institutions of knowledge that continue to have links with “Israeli” universities and companies and do not display a clear position against the genocide. The first one was McGill’s encampment, then others at various universities such as Toronto, Ottawa, British Columbia, Sherbrooke and Laval. The latter was immediately dismantled by force, which demonstrates, according to professors Nolywé Delannon, Louis-Philippe Lampron and Jesse Greener, in an op-ed published by Le Devoir on June 5, “that Université Laval has become a space for muzzling and judicializing democratic student life, a trend that the entire Quebec university community should be concerned about.”

At UQAM, an encampment called the Al Aqsa Popular University (APU) was set up from May 12 until June 6, 2024. Its major demands concerned the disclosure of all the links with the Zionist entity and the adoption of an academic boycott of “Israeli” universities by the entire Quebec university network, in addition to opposition to the judicialization of the struggle for Palestine and the abolition of the future Quebec Office in “Israel.”

The APU: an alternative to the university?

Starting from the first days, workshops and teach-ins open to the public took place outside the barricades of the encampment. Over almost one month, critical content was delivered on the history of Palestine, the history of campus occupations, information on rights in cases of arrest and detention, digital resistance, climate justice, collective gardening sessions and healing circles, storytelling, movie screenings, revolutionary singing, music and much more.

This emerged following a collective reflection on the importance of offering critical content, particularly focused on Palestine but not only, to attract sympathizers to the cause, educate the less knowledgeable and keep the encampers in continuous learning and contact with the wider public. I was part of the programming team for these different workshops and events.

As at McGill encampment, we also had a library, with many books, and a space for reading and reading circles.

The tranquility of the atmosphere and space were sometimes disturbed by the hostile looks and comments of some UQAM security officers, but especially by particular police interventions.

Violence, surveillance and sense making

Two important moments in the history of the encampment seem to me to be worth noting: two serious clashes or two moments of police brutality with quite serious consequences. These are moments when the encampers tried to occupy the street and faced police violence in the form of pepper spray, beatings, point-blank projectiles and an arrest. This highlighted that barricading oneself in a specific space is disturbing, but occupying public space, making oneself visible and making one’s cause accessible are more disturbing to the State.

The first moment concerned the formation of a block in the street, the other was the open protest demonstration following the dismantling of the encampment, on June 6, 2024, which aimed to take the cause elsewhere and headed towards other liberated zones, as campers like to call them, such as McGill’s.

Increased surveillance (drones, a strong daily police presence, UQAM security agents on the lookout, etc.) had accompanied the experience of the encampment.

Gaining access to what was happening in the encampment, in particular by installing surveillance cameras all around and sending guards to make frequent rounds, ever closer to the perimeter of the “Free Zone”, had, for example, become an obsession of UQAM. It was not uncommon for us to be in a general assembly, or simply reading a book, chatting in a small group or emptying the trash, and to have a guard spying on our various gestures, to discover a new surveillance camera placed so as to see what was under the tarpaulins, and even to have a drone hovering above our heads.

Relations with UQAM’s administrators were also tense, the latter using delegitimizing words in its press releases, such as “threatening”, “masked”, etc., playing the same game of referring to an imaginary around violence, even when it was the encampers who were suffering it. As Patricia Hill Collins says in “The Tie That Binds: Race, Gender, and US Violence’ (1998, p.922), “definitions of violence lie not in acts themselves but in how groups controlling positions of authority conceptualize such acts.” In fact, UQAM relied on the production of threats to gain legitimacy, and tried to shape public discourse in such a way as to stigmatize the campers.

Another episode of violence: the doxing that some encampers suffered by far-right media outlets that published their photos and certain personal information about them, trying to track them and putting their safety at risk. Doxing should be understood, as Douglas (2016, p.201) states, “as releasing publicly a type of identity knowledge about an individual (the subject of doxing) that establishes a verifiable connection between it and another type (or types) of identity knowledge about that person […] it utilizes documentary evidence of identity knowledge.”

As a form of intimidation, doxing “attempts to silence the subject and prevent her from participating in social, political, and public activity” (Douglas, 2016, p.206).

The violence of this act is measurable by the impacts and consequences it can cause.

Several after-effects remained among the activists and the consequences of certain violent acts, particularly doxing, may continue to manifest themselves, but we might also remember that, as Isabelle Sommier says in Political Violence and its Mourning (2008, p.58) : “living together physically repression unites, even constitutes the group; resisting marks a radical break with the values of the system, separates friends from enemies”.

Following the demonstration, and as announced in a press release on May 30, 2024, the APU encampment dismantled, considering that it had made considerable gains and calling for the continuation of the struggle on all fronts. The UQAM Board of Directors had adopted a resolution that seemed to lead to an academic boycott.

Paradigm Shift

The struggle for Palestine since the beginning of the genocide in Gaza, through various tactics and means, has been accompanied by a paradigm shift translated by a change in slogans, now shaping the struggle around an imminent victory:

“From the river to the sea Palestine is almost free!”

“We will free Palestine within our lifetime!”

These are among the slogans most chanted in the streets of Quebec and Canada, which take us far from the discourse of defeat and the near impossibility of liberation without many concessions.

The growing movement around the encampments foreshadows the holding of other ones within and outside the university.

To report on these risky militant experiences, “militant ethnography” is particularly relevant because it offers an overview of the experience, from the inside, from the perspective and position of an “active political practitioner[s]” (Apoifis, 2024), while being accountable to the people who are part of the movement or structure. It also allows us to shed deep light on issues and methods of action that are not very accessible to researchers less involved in these movements, and who mobilize more “classical” methodologies.

Sonya Ben Yahmed

Sonya Ben Yahmed is a researcher and PhD graduate student of Université de Montréal.

Bio

Her multidisciplinary work addresses issues of gender, violence, power, body, language, and mobility, from an intersectional and decolonial perspective. She is the coordinator of the Gender (I)mobilities and Precarious Situation project, a Participatory Action Research, and a long-time community organizer in feminist and anti-capitalist and anti-racist movements, both in Tunisia and Quebec.

Notes

[1] In this regard, one can for example read the statement of Women of Diverse Origins: https://www.facebook.com/share/p/xBEdRP8vanZFeEKG/

[2] In terms of terminology, I prefer to use the notion, not very common in the West, of “Zionist entity”, instead of “Israel”, which is a translation from the Arabic of “Al kayan Al-Sohyuni”. This choice, also made by many pro-Palestinian groups, particularly in the Arab world, denotes the importance of emphasizing the illegitimacy and ephemeral nature of the Zionist state. It implies that it is a “temporary phenomenon haunted by something older and more lasting. It evokes Palestine even when describing the occupier” (Salaita, 2024).

At times, to make it easier to read, I may also use the word in quotation marks: “Israel”.

Editors’ Note: We encourage readers seeking more historical and contemporary context on the use of these terms to read Steve Salaita’s essay on this topic.

Works cited

Apoifis N. Anarchy in Athens: An Ethnography of Militancy, Emotions and Violence. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2016.

Awres, W. “Censure des voix palestiniennes et des pro-Palestine: une attaque féroce à la liberté d’expression.” Medfeminiswiya, October 23, 2023. https://medfeminiswiya.net/2023/10/23/censure-des-voix-palestiniennes-et-des-pro-palestine-une-attaque-feroce-a-la-liberte-dexpression/

Collins, P.H. “The Tie That Binds: Race, Gender and US Violence.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 21, no. 5 (1998), 917-938.

Delannon, N. et al. “Pour que cessent le musellement et la judiciarisation de la vie démocratique étudiante à l’Université Laval.” Le Devoir, June 5, 2024. https://www.ledevoir.com/opinion/idees/814294/idees-cessent-musellement-judiciarisation-vie-democratique-etudiante-universite-laval

Douglas, D.M. (2016). “Doxing: A Conceptual Analysis.” Ethics Inf Technol 18, 199–210.

Dupuis-déri, F. “Où sont les défenseurs de la liberté universitaire?” Le Devoir, January 25, 2024. https://www.ledevoir.com/opinion/idees/805939/education-ou-sont-defenseurs-liberte-universitaire

Ellis, C. et al. “Autoethnography: An Overview.” Historical Social Research 36, no. 4 (2011): 273-90.

Juris, J. “Practicing Militant Ethnography with the Movement for Global Resistance in Barcelona.” Pp. 164-78 in Shukaitis, S. and Graeber, D. (eds), Constituent Imaginations. Oakland, CA: AK Press, 2007

Keefer, M. 2024. “Knowing and not knowing: Canada, Indigenous Peoples, Israel, and Palestine.” Pp. 121-139 in Wills et al (eds), Advocating for Palestine in Canada: Histories, Movements, Action. Halifax and Winnipeg: Fernwood Publishing, 2024.

Mastracci, D. 2024. “Close-ups, media, non profits, campuses.” Pp. 145-162 in Wills et al (eds), Advocating for Palestine in Canada: Histories, Movements, Action. Halifax and Winnipeg: Fernwood Publishing, 2024.

Salaita, S. “Down with the Zionist Entity; Long Live “the Zionist Entity”.” Steve Salaita [blog], May 23, 2024. https://stevesalaita.com/down-with-the-zionist-entity-long-live-the-zionist-entity/

Sommier, I. La violence politique et son deuil. L’après 68 en France et en Italie. Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes, 2008.

Women of Diverse Origins. “WDO, firmly in solidarity with the Palestinian people and against any instrumentalization of the women’s cause.” Facebook post, February 28, 2024. https://www.facebook.com/share/p/xBEdRP8vanZFeEKG/

You may republish this article, either online and/or in print, under the Creative Commons CC BY-ND 4.0 license. We ask that you follow these simple guidelines to comply with the requirements of the license.

In short, you may not make edits beyond minor stylistic changes, and you must credit the author and note that the article was originally published on Home/Field.