By Chloe Tucker and Hugo Martínez

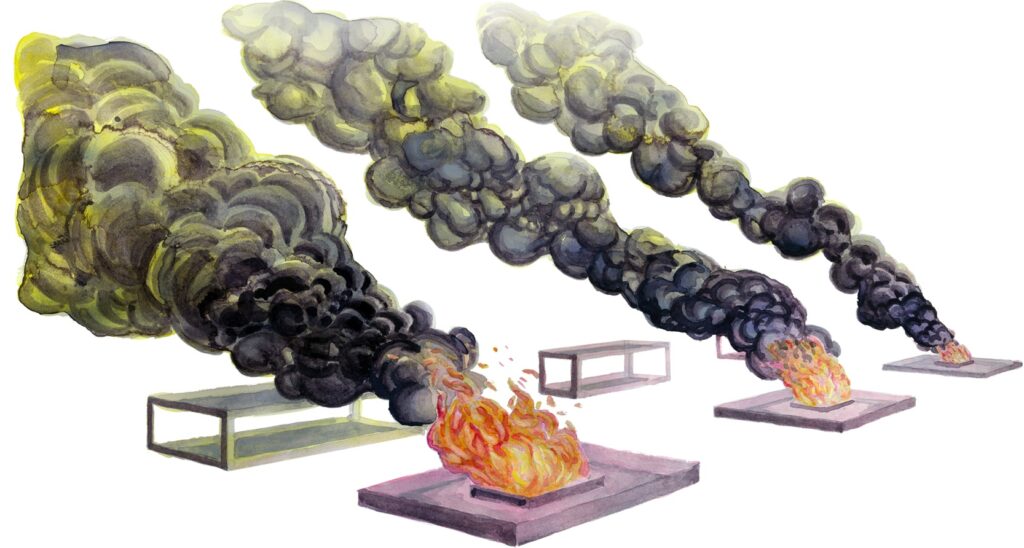

People who live near Colfax, Louisiana have been reporting increased incidence of skin conditions, lung cancer, asthma and respiratory diseases as business has ticked up at a nearby waste incineration plant (Richmond-Bryant et al. 2022; LSU Tumor Registry).[1] A fenced-off facility just outside of town holds the only EPA permit for open-air incineration of toxic materials, and Louisiana laws make it more cost-effective to dispose of them here than anywhere else (VICE 2022). The facility receives millions of pounds of toxic and hazardous waste materials from around the country—these materials include expired fireworks, “frictive” industrial byproducts, and expired military ordinance—and disposes of them by burning them in the open air (Lustgarden 2017).

Local organizing for environmental justice takes place in the small U.S. city that was home to one of the most violent white supremacist events in U.S. history: the Colfax Massacre of 1873. This piece combines selected photographs by Tulane’s Critical Media and Visualization Lab and watercolor portraits of Colfax and its residents by New Orleans-based artist Hugo Martínez.

When Colfax, Louisiana makes the news, it’s often for one of three reasons—the November Pecan Festival which draws 75,000 visitors to the town of 1,500, the deadly white supremacist violence of 1873, or the open-air hazardous waste incineration facility just outside the city limits[i].

In 2018, I received a fellowship from Tulane to work with the Louisiana Environmental Action Network, a coalition based in Baton Rouge. The staff there connected me to a fenceline community (a neighborhood adjacent to an industrial or polluting facility’s boundary fence), living on a bluff of the Red River just outside of Colfax. This community, The Rock, borders Clean Harbors-Colfax, the nation’s only commercial facility operating under a RCRA Part B, Subpart X permit: this permit makes the site the only place in the U.S. where hazardous waste can be burned directly into the open air. Next door, millions of pounds of “energetic hazardous waste” including expired fireworks, unused military explosives, and expired automotive airbags have been covered with diesel fuel, transported onto burn pads and set on fire.

Like other fenceline communities nationwide, The Rock’s residents are overwhelmingly low-income and disproportionately non-white: 58% percent of Colfax residents identify as Black, and 90% of the population lives below the federal poverty line.[ii] Unlike other fenceline communities, The Rock’s residents live five miles from the site of the 1873 Colfax Massacre, in which a white mob attacked and killed as many as 100 Black citizens who had occupied the courthouse to preserve their vote following a contested election. The Supreme Court’s refusal to punish white perpetrators effectively neutered the postwar Enforcement Acts against the KKK and ended Reconstruction.[iii]

I had only lived in New Orleans for a few months before the city made good on its pledge to remove Confederate monuments from public lands. Throughout the spring of 2017, my path across town crisscrossed protests and counter-protests ringing the monuments. I grew up white, female, and university-affiliated in Charlottesville, Virginia: the white supremacist Unite the Right rally was still sending shockwaves through my hometown when I drove four hours to central Louisiana to visit Colfax for the first time in 2019.

As Louisiana place names go, Grant Parish and its seat of Colfax stand out for their striking links to the Reconstruction Era: the place names honor the Union general/president and his vice-president respectively, and well into the 20th century, local white leaders remembered the period as a “carpetbag” occupation.[iv] More shame on me, then, that I did not dig into Colfax’s history before attending a community meeting of citizens organizing against the detonations going off hourly: like other people who write about Colfax but are not from the area, I failed to perceive the place in front of me as a palimpsest—which, of course, it always is. I failed to see the layers beneath: the events historian Eric Foner describes as “the bloodiest single instance of racial carnage in the Reconstruction era.”[v] Concerned only with contemporaneous evidence of environmental degradation and racism, I only saw what I looked for, and received answers to the questions that I asked, and so I left my first visit to Colfax: the most recent layer of what Rob Nixon terms the “slow violence” of toxic accretion in the bodies of fenceline communities.

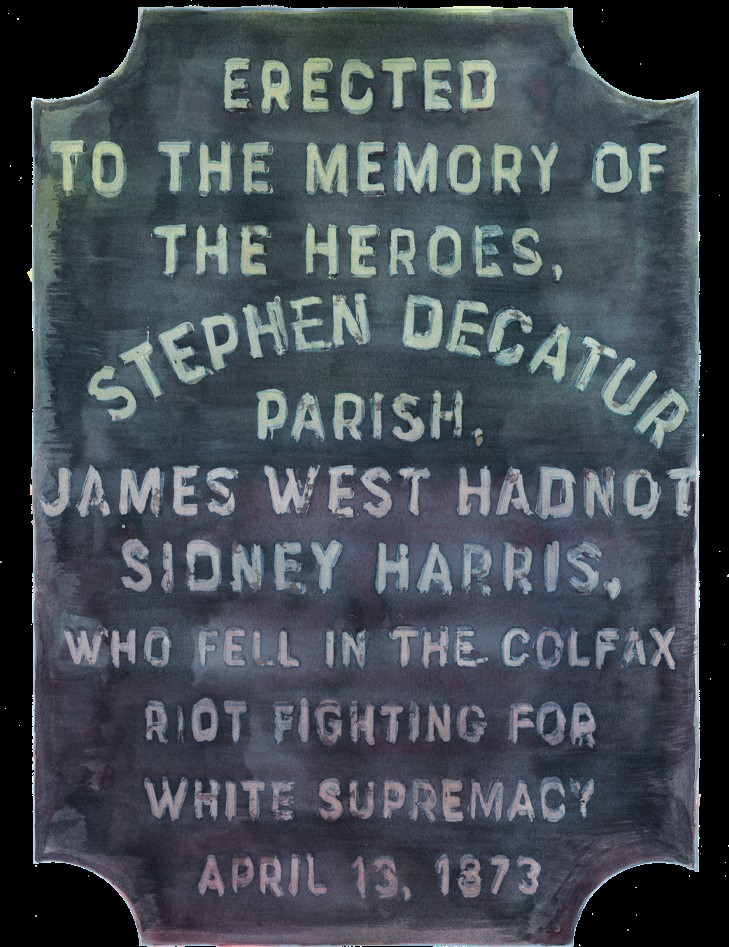

There in the center of town stood two monuments to the past which praised the massacre’s white perpetrators. In 2021, the state removed the official marker for the Colfax Massacre (which claimed the violence brought “an end to the era of carpetbag misrule in the South”),[vi] but the tall 1920s obelisk erected to the white dead still stands in a nearby cemetery. This spring, a memorial to the Black dead (who have remained unnamed and uncounted since the 1870s) was erected in the town’s fairgrounds, the site of the annual Pecan Festival.

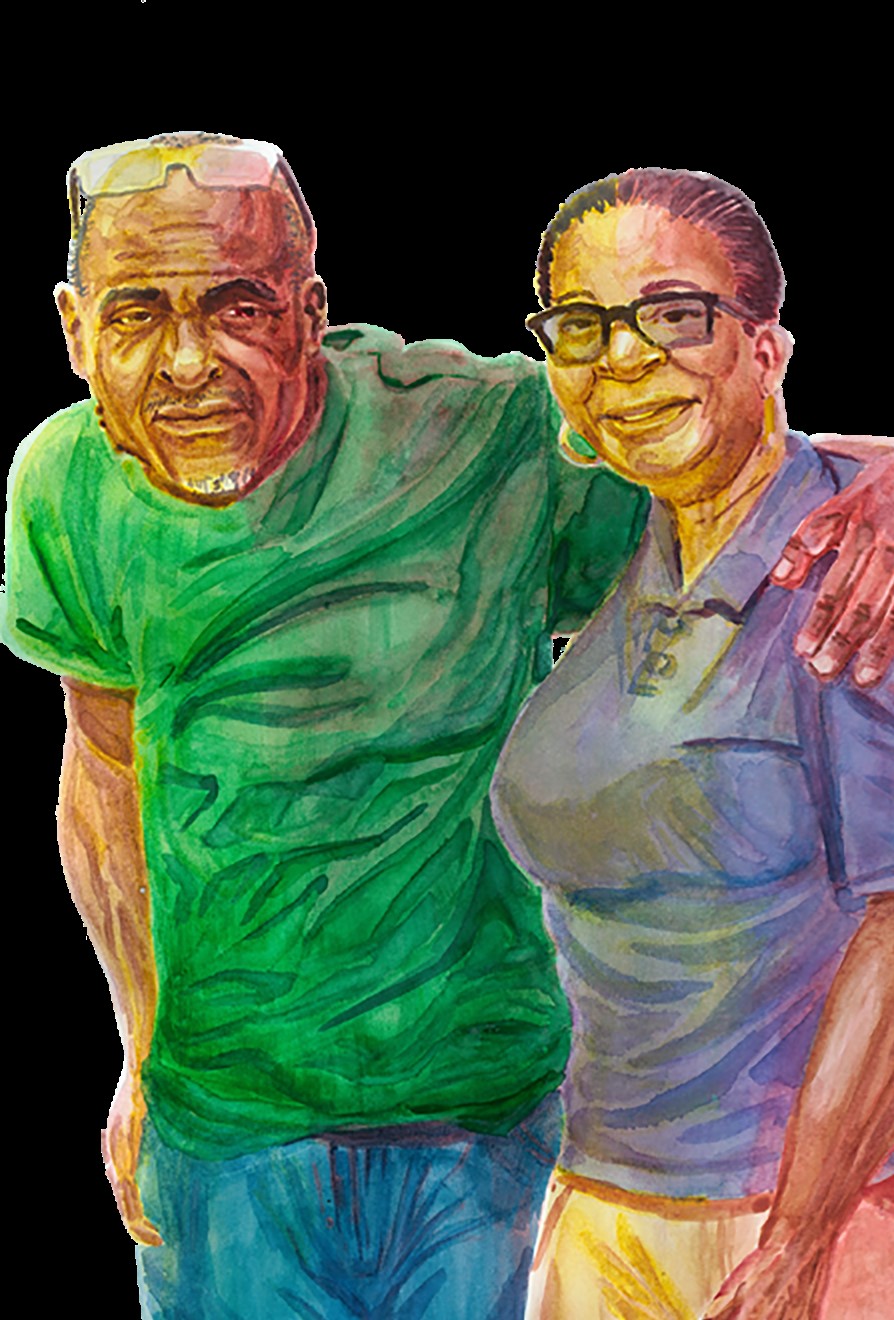

The Rock residents living near Clean Harbors’ Colfax facility did not address the past until I brought it up. They correctly assumed that I had arrived to their community to talk about the pressing issues impacting their daily lives: when I asked Louis Swafford, pastor of the Old Morning Star Baptist Church, about the memory of violence from the Colfax Massacre nearly 150 years ago, he replied that “It’s never been talked, never talked about” Perhaps this is because the massacre loomed so large that it was not to be discussed, not to be talked about, and something that would hinder and distract from the urgent work and organizing directly before them. As Pastor Swafford phrased it to me in 2020,

There’s some things we could tell you about the racist things that there is just in this little community, that they went through. But that’s just part of life, you know? We’ve overcome that! […] See, time brings on the change. Now we’re working together to try and solve some pollution [and] to help everybody. It’s not just us! We’ll say the African-American community, but it’s not just the African-American community, it’s the whole town of Colfax.

Louis Swafford and Loretha Swafford, 2020

Hugo Martínez, watercolor 2021

Chloe Tucker, photograph, 2020, Courtesy Tulane-CVML

The smoke from this open-air incineration of hazardous materials enters the open air. Louisiana’s environmental laws make open burning up 2,000% cheaper to haul and burn hazardous waste at Clean Harbors’ Colfax facility than in contained burned systems (VICE 2022).[vii] In 2012, nearly 100 tons of unused munitions and propellant exploded at Camp Minden and evacuated a nearby town. Thousands of tons of remaining expired ordinance were rerouted to Clean Harbors-Colfax (Lustgarden 2017). Since then, Colfax residents have reported higher incidence of thyroid illnesses, skin conditions and respiratory diseases (Richmond-Bryant et al. 2022, LSU Tumor Registry 2019).[viii] Today, parents discourage their children from playing outdoors. Two Rock residents who have young children living in their home describe their understanding that this crisis has brought other dangers over the threshold of their doors, endangering their families where they live.

I’m prior military…[and] they’re over there blowing up those same bombs that we take overseas to kill our enemies in this community–what do you think they’re doing to us? It’s not the sound from the bombs that’s killing the people, it’s the chemicals that’s in the bomb. – Rock Resident, 2020.

We have a few white people it’s affecting. But if you look at the majority of it, it’s mostly Black. We outnumber the white, big population, you know, in the neighborhood where Clean Harbors is at […] If I can put it in a way…If we were the white people, and the white people were, you know, just vice versa it around so it was just a few little Black people, I don’t believe they’d never made it [burn] there. They would have never made it there. But they already know: if the Black people get to complaining, unless you get some white people in there to push it, ain’t much gonna be did. Ain’t much gonna be did. – Earl Swafford, Colfax resident, 2020

In the fall of 2019 and the pre-pandemic months of 2020, I made a handful of trips up to Colfax to attend community meetings and connect with residents. The people I spoke with asked me to help them share their story more broadly. In early January, I led a group from Tulane’s Critical Visualization and Media Lab: we brought cameras and audio recorders with us, taking oral histories and portraits. But COVID-19 hit New Orleans early and hard, and given the prevalence of respiratory illness among Rock residents, I did not return to Colfax until summer 2021.

That summer, Tulane funders reached out with an opportunity to our cohort: they provided the opportunity to work with New Orleans-based watercolor artist Hugo Martínez to help illustrate our community-engaged research. I talked fast in our first meeting, feeling nervous that I was seeing clear and urgent links between the historic direct violence and contemporary slow violence of the present, that had not been joined in journalism or scholarship. Colfax’s crises layered and unlayered themselves: Colfax was still a small city with monuments to white supremacist violence in its town center. Colfax leadership had a history of upholding white power over Black citizens. People living near Clean Harbors’ facility stayed inside because the air was no longer safe. A company headquartered in Boston is responsible for harm to local residents. Black and white citizens in Colfax were organizing together, finding common cause and fighting for the right to reside in their homes without getting sick.

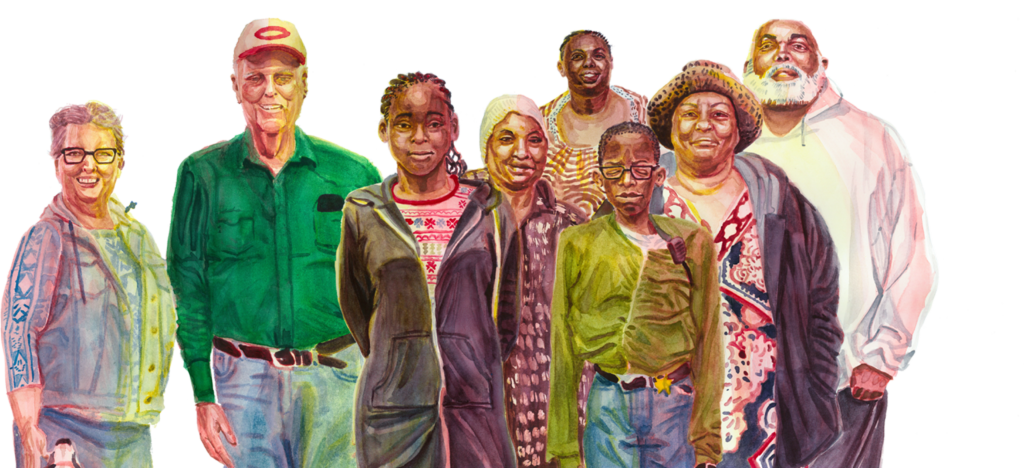

Hugo’s work draws these links together. His paintings emerged through our conversations and his own study of the photographs and interviews with Rock residents, and they begin to stitch a timescale of compounding crises. The piece honors how Colfax residents navigate the slow violence of racial health disparities, legacies of enforced segregation, and spatialized environmental injustices. Animated by Hugo, these watercolors center Colfax residents and place them together in front of the Old Morning Star Church on the Rock, where they meet to organize. Meanwhile, the hourly detonations continue, and Clean Harbors reported adjusted 2022 earnings over $1 billion. His illustrations place them where they live: in the middle of the complex crises.

Colfax community, watercolor, digitized, animated by Hugo Martínez, 2022

Hugo Martínez

Hugo Martínez is a New Orleans resident focusing on narrative art via comics and animation.

Bio

Concentrating on narratives of struggle, identity and liberation as the son of a guerrilla Sandinista mother, the artist wrestles with what resistance to oppression means in today’s world. Primarily self-published, Hugo recently worked on Wake: The Hidden History of Women Slave Revolts, a collaborative narration of resistance and the process of uncovering and telling history, with Dr. Rebecca Hall. The artist’s aim is to highlight and scrutinize the meaning of revolution, from the intimate experiences of the individual to the collective.

Chloe Tucker

Chloe Tucker is a doctoral candidate in sociology at Tulane’s interdisciplinary City, Culture and Community program.

Bio

Her research focuses on the experience of disasters in home places and the uncomfortable “home truths” they illuminate about climate crisis and environmental degradation.

References Cited

[i] Lustgarden, A. 2017. “Kaboom Town”. Pro Publica. July 21, 2017. https://www.propublica.org/article/military-pollution-toxic-burns-colfax-louisiana

[ii] Richmond-Bryant, J., M. Odera, W. Subra, B. Vallee, C. Tucker, C. Oliver, A. Wilson, J. Tran, B. Kelley, J. A. Cramer, J. Irving, C. Guo, and M. Reams. 2022. “A Community-integrated Geographic Information System Study of Air Pollution Exposure Impacts in Colfax, LA”. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.19790029.v1

[iii] Pope, J.G. 2014. “Snubbed Landmark: Why United States v. Cruikshank (1876) Belongs at the Heart of the American Constitutional Canon.” Harvard Civil Rights-Civil Liberties Law Review (CR-CL), Vol 49, pp. 385-447 https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2343932

[iv] Briggs, W. and Jon Krakauer. “The Massacre that Emboldened White Supremacists“ August 28, 2020. New York Times [online] https://www.nytimes.com/2020/08/28/opinion/black-lives-civil-rights.html

[v] Quoted in the Zinn Education Project. 2023. “Today in History–April 13, 1873: Colfax Massacre” The Zinn Education Project [online]. https://zinnedproject.org/news/tdih/colfax-massacre

[vi] Briggs and Krakauer 2020

[vii] VICE Media. 2022. “The U.S. Military Contracted Burn Pits No One is Talking About”. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cYZkvmEjvuI

[viii] Louisiana Department of Health. 2019. “Cancer Incidence Review of Colfax, LA and Grant Parish”. March 7, 2019. https://ldh.la.gov/assets/docs/HR226_031519.pdf

You may republish this article, either online and/or in print, under the Creative Commons CC BY-ND 4.0 license. We ask that you follow these simple guidelines to comply with the requirements of the license.

In short, you may not make edits beyond minor stylistic changes, and you must credit the author and note that the article was originally published on Home/Field.

Support, materials, and funding for this research and collaboration made possible through the Tulane-Mellon Community Engaged Fellowship and the Tulane Critical Visual Media Lab. All photo credits: Tulane Critical Visual Media Lab, 2020. All painting and video credits: Hugo Martínez, 2022.

To see more of Hugo’s work in print, visit his illustrator page.

To hear voices of Colfax residents organizing around air quality, watch the 2022 documentary produced VICE Media linked in footnotes.