By Yasmen Abuzaid, Dency Amalraj, and Lisa Howell

Introduction

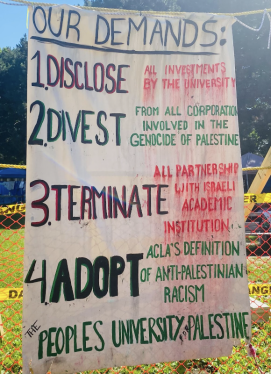

On April 29, 2024, students at the University of Ottawa (uOttawa) set up a sit-in on the lawn of Tabaret Hall[i], which houses the university’s central administrative offices and occupies the unsurrendered, ancestral land of the Anishinaabe Algonquin peoples, in what some now call Canada[ii]. The students, including those from nearby Carleton University and Algonquin College, returned the next day, and established an encampment that evening, in solidarity with universities across Canada, the United States, and around the world. In a statement released by INSAF uOttawa (Integrity not spite against Falastine), Occupy Tabaret aimed to “occupy space, popularize our education, and demand accountability from our university for, in their own, enabling the genocide of the Palestinian people, and families of their own students” (INSAF, 2024a). Nearly six months earlier, INSAF had released four demands, namely that the University of Ottawa fully disclose its updated investment holdings list; divest its pension fund from corporations and institutions that facilitate Israel’s occupation of Palestine and genocide in Gaza; commit to reviewing and accordingly breaking off relationships with academic Zionist institutions, and to adopt the Arab Canadian Lawyers Associations’ definition of Anti-Palestinian Racism.

Two weeks later, on May 15, members of INSAF, Students for Justice in Palestine Carleton (SJP Carleton), Independent Jewish Voices Carleton (IJV Carleton), and the Palestinian Students Association at the University of Ottawa (PSA uOttawa) held a press conference reinstating their demands and updating the encampment and community members on negotiations with the uOttawa administration. In a meeting that afternoon, the university agreed to give a timeline for disclosure of its investments by Friday, May 17 and agreed to discuss adopting the Arab Canadian Lawyers Association’s definition of anti-Palestinian racism. INSAF president Sumayya Kheireddine said:

Should the murder of over 40 000 Palestinians in Gaza not be considered a legitimate cause for immediate divestment? We will remain firmly rooted here demanding that the [U of O] immediately prioritise human life and support their students in standing on the right side of history…our power is in numbers, our power is together until liberation and return. (Achar, 2024, para.10)

Nir Hagigi, president of Independent Jewish Voices (IJV) Carleton, poignantly asked that after “eight months of enduring such horrors, why is it unreasonable for us to insist…that they immediately disassociate themselves from the perpetrators of this genocide?” (Achar, 2024, para. 11). Unfortunately, negotiations went nowhere over the next month. Students walked away often feeling infantilized and unheard, despite coming to the negotiation table in good faith. Throughout negotiations, students offered various ways for the administration to meet their demands, from simple policy changes to the acknowledgement of anti-Palestinian racism. Unfortunately, “the university responded by stalling and hiding behind bureaucracies, stating they cannot take a stance on this matter” (Insaf, 2024b). On July 9, faced with the reality that negotiations were at an impasse, and amid threats of police action, the students decided to end the 72-day encampment. They left with a promise to return and a statement that in part affirmed:

We the students, began this Occupy Tabaret encampment on Tabaret lawn over two months ago because we refuse to allow the University of Ottawa to continue being complicit in the genocide in Gaza and the continued occupation of Palestine…We know, and the world has seen, that what is happening in Palestine is not some complicated philosophical concept or a distant “conflict” to take financial advantage of. What is happening in Palestine is real. It is real occupation, real apartheid, and a very real genocide happening to real people. And what does uOttawa have to say about this? Well, they don’t know if the right to academic freedom supersedes the right to life. You have not and you will not break our spirits. And as we have said from day 1, we will not stop, we will not rest. We will be back. (Insaf, 2024c)

As we, students and a professor, reflect on the ten weeks of the encampment, we are awash in emotions of gratitude and immense hope. The students who led Occupy Tabaret created a transformative educational space where community members, faculty, labour organizers, visitors, activists, and Ottawans came together to learn and unlearn. Teach-ins educated people about topics on settler colonialism from Turtle Island to Palestine; about police brutality and engineering and the military complex; we learned about issues ranging from the Boycott, Divest, and Sanction (BDS) movement to the liberation and resistance struggles in Algeria, Vietnam, Cuba, and of the Māori people. Lectures on the history of Palestine, on Zionism, on antisemitism, on disability awareness in Palestine and Anishinaabe perspectives on solidarity were where we found each other on many evenings on the grounds of the liberated zone. People of all faiths, and of no faith at all gathered on lawn chairs and blankets, and during downpours and heatwaves to listen and learn. Over the ten weeks of the encampment, the liberated zone hosted workshops on beading, Tatreez (a form of traditional Palestinian embroidery), Palestinian resistance art, Arabic lessons, poetry, writing, and de-escalation training. There were several film screenings, including Where the Olive Trees Weep, Tantura, Wanted 18 and a Nakba docuseries produced by Al Jazeera. The liberated lawns brought people into community – to break bread together, to pray together as many faiths (Muslim, Christian, and Jewish prayers were heard often), to sit in conversation circles, and to observe Eid. Teach-ins, read-ins, artbuilds, fireside chats, chant circles, a children’s zone, and the people’s library were places where we realised that the relationships between liberation movements across the globe are inexplicably interconnected and similarly silenced by colonialism, capitalism, and imperialism.

In what follows, we offer a series of vignettes that interweave our distinct understandings and positionalities in the hopes of conveying a sense of the complexity and layers of experiences at the encampment. First, we provide brief biographies to situate ourselves on this land. Yasmen is an angry Palestinian woman who lives as a settler on stolen Algonquin land. Her family was displaced from Qalqilya and Bal’a during the Nakba in 1967. They fled to Irbid, Jordan, where both her parents were born. Later in their lives, Yasmen’s parents immigrated to the land of the Three Fires Confederacy where she was born and raised. She’s spent the past two years on Algonquin land, being a friend, tatreez artist, teacher, beginner activist, and self-proclaimed neighbourhood cat lady. Dency is a settler Canadian of south Indian descent who lives and works on the unceded and ancestral territories of the Anishinaabe Algonquin Territory. She is a comrade, friend, resistance fighter, teacher with the Ottawa-Carleton District School Board and a beloved member of the student encampment at Tabaret Lawn. Lisa is a settler Canadian of northern European descent who lives and works on the unceded and ancestral territories of the Anishinaabe Algonquin. She is mother, sister, aunt, partner, friend, bicycle-rider, gardener, teacher, activist, and professor with the Faculty of Education and a member of Faculty for Palestine at the University of Ottawa.

Vignettes: A series of three voices over time from the liberated zone

Yasmen: We keep us safe

On day two of what was soon to become the official encampment, I turned my laptop on and waited for my therapist. We usually begin each session with pleasantries and small talk so I can draw out saying what I’m struggling with. Today though, I can’t wait for her to stop talking. I’m too anxious. When she asks me how I am, I blurt: “I might get arrested tonight.” She waits for the gotcha moment. There is none.

I explain that yesterday, following the lead of students from universities like Columbia, we set up a 9AM to 9PM sit-in. April 29 was also the start of my first real teacher job, and I had gone directly after work. This evening at 7PM, a small group of us agreed to sneak tents onto the lawn and officially set up a camp. uOttawa threatened that an encampment could “carry serious consequences” for students involved (uOttawa, 2024). There was a chance I’d be arrested for sleeping on the lawn, or even setting up tents. I was willing to do it, not because I wanted to, but because I morally felt like I had no choice. The weekly protests, then entering their 7th month, had done very little. It was time to escalate. My therapist wished me the best and told me to tell her if I was okay the next morning.

After my session, I headed down to the lawn. Our small group met at 4:30, went over our plan, and then broke off to not seem too suspicious. I knew that that I had no choice but to do be exactly where I was. I owed it to the then 34 000+ martyrs to try to divert the money that was raining on them in the form of bombs (Siddiqui, 2024).

When 7PM came we sprang into action. I had never set up a tent in my life, and I proved to be quite useless at anything other than pushing pegs into the ground. Around us, the community created a circle to protect us while chanting liberation slogans. In between my shaking hands and racing thoughts, I remember thinking “we protect each other.”

People brought us sleeping bags and food as soon as they heard what we had done. I was offered food, tea, and loving words. I slept that night without being arrested, but shivered throughout the cold, wet night. I made it to work, and then went home sick. I never slept in a tent again at the encampment so I could work effectively in the morning. Millions of Palestinians since 1948 have never had the choice between a warm home or the rocky earth.

Lisa: Power washing and Genocide

It’s Day 15 here at the liberated zone, a beautiful day in May 2024. The sky is bright blue, and there is a slight breeze. Tabaret Hall, with its imposing and regal colonial structure, provides a juxtaposing backdrop to the encampment. I am marshalling today, keeping watch over the north entrance. It’s quiet, though I’ve had one person stop and ask me if I “love Hamas” and don’t I “care that Hamas raped and killed Israeli girls? I have a daughter, you know.” I wonder if he noticed that I am a woman. The conflation of Palestinian solidarity with terrorism is endemic. I don’t respond to this nonsense.

As the afternoon progresses, I watch as students and community members install two -metre-tall boards that they fasten banners on. Each banner honours the names of the martyrs who have been killed by Israel since October 7, 2023. There are too many banners, each with long lists of too many names of infants, children, and youth. Together, there are thousands of names of young people who will never grow to be the age I am now, or even the age of most of the students who are part of this community. I feel this acutely as my eyes take in their names. I feel a profound ache in my chest, the constriction of my throat. Hot tears fall from my eyes and onto my barefooted toes.

At the same time the banners are being installed, contractors hired by the University of Ottawa are power washing the front steps, columns, and sidewalks of Tabaret. They are attempting to erase chalk messages and drawings with their “powerful” tools. The colourful drawings are of hearts, Palestinian flags, and messages, which convey statements such as, “Free Palestine” “Resistance until Return” and “Eyes on Gaza.” Somehow, these sentiments for peace in chalk are offensive to the university.

As I sit and watch this unfold – the community members and students raising the banners to honour the thousands of children killed in Gaza – and the contractors power washing the chalk messages – I wonder how such contradictions can exist simultaneously in space and time. I don’t have any answers…only feelings of dissonance and despair.

Dency: Lovenote

Marshalling was my favourite part of the encampment. The Palestinian Youth Movement (PYM) oversaw security for Occupy Tabaret. I received training from PYM organizers on how to be a marshall the first night after I stayed in a tent at the encampment four days after it had begun. Marshalling came with its highs and lows. One moment I’d be laughing my guts out and out of breath talking about my childhood with my friends and the next I’d be dealing with a white male cutting down our tarp art wall filled with resistance messages. I never gave up though, I never wanted to…

Men, women, and children in Gaza face struggles every day that I could never imagine. University of Ottawa funds this genocide. This genocide that has taken over 45 000 lives, over 15 000 children at the time of this writing. I stared at the children’s martyrs’ names day in and out when I’d marshall. There were four main marshall stations throughout most of the camp: Laurier (South), Wilbrod (North), Cumberland (East), and Tent Entrance. My favourite was Laurier. I loved watching the cars come by at all hours. Some of them honked in the tune of “Free, Free Palestine”, others yelled “HAMAS ARE TERRORISTS! YOU ARE TERRORISTS!” Students and community members walked by too and some of them struck up conversations with me or me with them. My favourite conversations as a marshall were ones where education was involved – education about Gaza, education about the horrors happening in Gaza at this moment, the difference between Anti-Zionism and Antisemitism, the active role our institutions, especially uOttawa, and our government play in carrying out this genocide with imperialist powers such as the US, UK, and the Zionist state of Israel.

I took the leadership role as a marshall lead to help organise marshalling better. I really enjoyed the extra responsibility and sense of pride and duty that it gave me. Communication was key but it was hard with everyone’s busy schedules. It didn’t matter though because whatever happened we had each other’s back, we kept each other safe.

I met the coolest people ever as a marshall and as a student of the encampment…people that I hope to always keep in touch with for the rest of my life. I learned about their own struggles, their nation’s struggles, and their families’ struggles. I told them about my own struggles too. Together, we connected how all our struggles are one with the Palestinian struggle and the Palestinian Intifada.

Camp taught me resistance-resistance as a child, resistance as a brown woman, resistance as a queer person, resistance as a teacher, resistance as a student, and most importantly what it means to be a resistance fighter as a Palestinian.

Yasmen: All your comrades are here

The morning of Day 40 of the encampment, I am graduating with my Bachelor of Education, a short walk away from the Liberated Zone. It is a moment I have been waiting for since 5-year-old Yasmen decided to be a teacher. Instead, I spend most of it in discomfort and anxiety, faced with the reality that most of my classmates who will soon tell interviewers about their commitment to equity do not care about genocide happening.

During the ceremony, a fellow encampment participant named Tom heckles President Jacques Frémont and calls on him to divest. Frémont tells Tom that he has heard him and launches into a lecture about respecting academic discourse. I wonder: if heckling is disrespectful, then what can funding genocide be called? If we need to allow for academic discourse, then where should the students in Gaza gather to talk when they have no post-secondary institutions left?

I am comforted by the presence of my friend Azeeza, who is in the audience as my guest. We’ve become friends at the encampment after we co-led a discussion about white supremacy culture. In the short time I have known her, I already consider her a closer friend than almost everyone in the room. Tom and another participant-classmate comfort me too. They both use their moment on the stage to pull out hidden protest signs and risk getting kicked out of the ceremony. After I cross the stage waving a small Palestinian flag that I unsuccessfully try to hand over to Frémont, I run into the arms of Lisa, the only professor who is wearing a keffiyeh. We both hug knowing that the embrace is about more than me graduating. Afterwards, I head to the encampment for breakfast. At this point, my whole life is centred around the encampment. The other things I do-waiting for the bus, going to work, chores, sleeping, graduating, are just things I do until I can go back to the encampment.

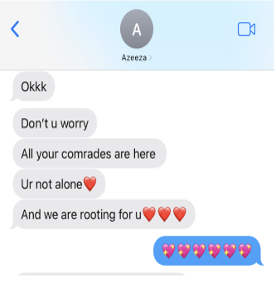

The next day, I am back on the lawn, grabbing fake roses with QR codes tied to the stems. The QR codes have information about our encampment and an invitation to join. The plan is to give them to graduates after their ceremony. The afternoon marshalling shift that I took on went well, so I invite a few friends to join me on the evening one. As I wait in front of the steps of Hind’s Hall for my friends, I begin to overhear a man talking to some of the uncles. It starts off innocently enough, but then turns into him claiming that Israel doesn’t kill innocent civilians. I feel a sense of anger and panic, so I put in Air pods and blast music to drown him out, but the damage is done. I am unable to talk to anyone properly that night, and it is Azeeza that comforts me again (Image 4).

The divide between these two worlds is something I have not figured out how to cope with and I’m not sure I ever will. On one hand, there is a world of people willing to risk their entire lives for Gaza. On the other, there is a world that perpetuates genocide, knowingly or carelessly. I don’t know how to operate in the second one anymore.

Lisa: Of knowing beyond the boundaries

It is Day 47, and the lawns of the People’s University for Gaza are full of all kinds. I notice a group of young people having a picnic underneath a canopy. In another area of the camp, a professor conducts a class. There is a new children’s zone, with a child–sized wooden picnic table, colouring pages, and a few books. I am writing a book chapter about student and youth activism in Canada, related to structural discrimination against First Nations children and their families. Under a shady tree, a young woman sits beading a Palestinian flag. The person beside her is reading Edward Said’s “Culture and Imperialism”. As a teacher, these scenes uphold my belief that educative spaces, when co-created amongst community, are sites of and for transformation. I am reminded of bell hooks, who wrote in Teaching to Transgress that “the classroom remains the most radical space of possibility in the academy… Urging all of us to open our minds and hearts so that we can know beyond the boundaries of what is acceptable, so that we can think and rethink, so that we can create new visions” (1994, p. 12). The encampment has become a classroom space of radical possibilities, of love and community, of boundary-unmaking and the remaking of relations.

It’s also a space of profound sadness. We are here because there is a genocide unfolding in front of our eyes. We are sitting, standing, stomping, chanting, yelling, sleeping, living, weeping, breathing, on this lawn because we cannot – we will not – be silent in the face of genocide. We are here because the Israeli Occupation Forces have dropped 45 000 bombs on Gaza during the first 89 days of conflict (Humanity and Inclusion International, 2024). In case, like me, that number is beyond your comprehension, try envisioning 505 bombings a day, or 21 bombings per hour. I. Can’t. Imagine. I can’t begin to grasp that horror. But I also can’t be complicit in the genocide of the Palestinian people, as a Canadian, as a human being, and as an academic. As a teacher – a professor of education – I thrive when I feel that I am supporting, challenging, and uplifting my students. It is a privilege teach students to read, think, and discuss transformative pedagogies, critical theories, global and urban educational contexts, race and racisms, and knowledge(s). My academic colleagues in Gaza don’t have these spaces anymore; Gaza’s twelve universities have been partially or fully demolished by Israel’s constant and murderous bombardments since October 7, 2023. The convocations that I’ve witnessed here over the last number of days – the thousands of students crossing the stage to mark and celebrate their accomplishments, the delighted family members holding flowers and snapping photographs, the bright smiles of students knowing that the years of study that have led to these moments are now complete – none of these rites of passage will take place in Gaza this year. Experts have warned that scholasticide, a term that refers to the systemic obliteration of education through the arrest, detention or killing of teachers, students and staff, and the destruction of educational infrastructure (United Nations, 2024) is occurring in Gaza.

And so, on June 14, 2024, Faculty for Palestine Ottawa organised a convocation vigil for the students of Gaza at Occupy Tabaret. Faculty members, myself included, silently robed and walked toward the steps of Tabaret Hall, where 50 chairs, each adorned with a red rose, a diploma, and a graduation cap, sat vacant, unoccupied, desolate. As I walked among these chairs, pieces of my heart broke and fell onto the rose petals along the path.

Concluding thoughts

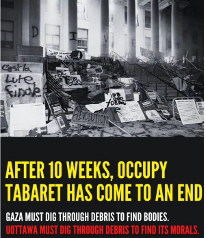

As the end of June approached, negotiations between uOttawa and the students reached a standstill. In a meeting on July 4, student representatives of the uOttawa encampment met with the administration to discuss a way forward. The students asked a series of questions including, “Why won’t you cut off relationships with universities when you know that they’re directly committing genocide through their military?” uOttawa administrative representatives answered, “We won’t cut off relationships because we explained to you that it is an issue of academic freedom” (Insaf, 2024d). It was clear from this answer, and others, that the University of Ottawa was unwilling to disclose or divest in genocide, cut ties with Israeli institutions, or adopt the Arab Canadian Lawyers Associations’ definition of Anti-Palestinian Racism. Talk of an eviction notice and the threat of an injunction weighted heavily on the student’s decision to conclude the encampment. Ultimately, students decided that the encampment was no longer a useful tool in the fight for their demands or the liberation of Palestine at large. The idea was not to give up, but rather, it was to leave a final message to tell the University they’d be back, but with different tactics. On the evening of July 9, 2024, a group of students stacked tents, tarps, tables, chairs, rope, garbage, recycling – some of the remnants of the weeks long encampment – on the steps of Tabaret Hall. Their message was not subtle: Gaza must dig through debris to find bodies. uOttawa must dig through debris to find its morals.

A few days after the encampment ended, Yasmen and Lisa met for lunch at a local restaurant that had just hosted an art show called “Posters for Palestine”. We spoke about our gratitude for the relationships we formed with fellow activists over the ten weeks of the encampment. We discussed the force and intensity of solidarity, camaraderie, community, and activism. We mourned the loss of respect or intimacy with people we called friends or community members who hadn’t showed up to the encampment. We reminisced over memories of breaking bread together on the lawns of the liberated zone, about learning and unlearning during workshops, teach-ins, and artbuilds. We both lamented the loss of the radical space of liberation and possibilities, of reimagining a world where Palestine is free, where Palestinian children are able to grow up safely, with dignity, self-determination, and sovereignty. We also spoke of a more immediate future: what was next for Palestine organising at uOttawa? The people who regularly attended the encampment across its entire existence were determined to keep fighting, but there were no plans in place yet. It was important for everyone to take time to rest, but there was a fear in the air that the community formed on the lawn would disappear. As I (Yasmen) write this, it still sometimes feels like the encampment was this dream that wasn’t quite real. There’s something worth noting about the fact our 72-day occupation did not even represent one day for each year of the 76-year occupation of Palestine.

Universities, both here on Turtle Island and across the world, must find the moral courage and sense of urgent responsibility to immediately divest from all companies and industries that are involved in harmful, genocidal, and otherwise unethical practices. These include arms manufacturers and corporations that, through their policies and operations, violate the rights of people guaranteed under the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the Convention on the Rights of the Child, and the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

In May 2023, Nahlah Ayed, host of IDEAS (a CBC radio program and podcast), moderated a public discussion at the University of Regina focused on the question: What are universities for? Linda Tuhiwai Smith, a professor at Te Whare Wānanga o Awanuiārangi in New Zealand said, “One of the interesting things about universities is they’re not good at letting go of some ideas. At one level they are about change, but [at] another level they’re about the status quo” (Carty, 2023, para. 12-13). The encampment movement across university campuses around the world has vigorously demonstrated that the status quo is diminished. Instead, the encampments have provided a radical (re)envisioning of expectations and ideologies about education and educational institutions, their investments, and their ethical commitments to their students, staff, and faculty, both present and in the future. Disclose, divest. We will not stop; we will not rest.

References Cited

Achar, K.V. (2024, May 16). University agrees to give timeline for disclosure of investments: Day 17 recap. Fulcrum. https://thefulcrum.ca/news/university-agrees-to-give-timeline-for-disclosure-of-investments-day-17-recap/âpihtawikosisân. (2016, September 23). Beyond territorial acknowledgements. Law, Language, Culture. https://apihtawikosisan.com/2016/09/beyond-territorial-acknowledgments/

Carty, M. (2023, September 5). What’s the point of university? IDEAS

(CBC). https://www.cbc.ca/radio/ideas/universities-moderated-discussion-university-of-regina-1.6946951

Hooks, Bell. (1994). Teaching to transgress education as the practice of freedom. Routledge

Humanity and Inclusion International. (2024, March 6). Bombings in populated areas: new extreme reached in Gaza. News-Occupied Palestinian Territories. https://www.hi.org/en/news/bombings-in-populated-areas–a-new-extreme-reached-in-gaza

INSAF. (2024a). Why Occupy Tabaret? Occupy Tabaret and the Popular University for Gaza. https://insafuo.com/occupy-tabaret-and-the-popular-university-for-gaza

INSAF[@Insafuotttawa]. (2024b, July 10). After 10 weeks, Occupy Tabaret has come to an end. [Photograph]. Instagram. https://www.instagram.com/p/C9QMdQURP_D/

INSAF [@Insafuottawa]. (2024c, July 9). We the students, began this Occupy Tabaret encampment on Tabaret lawn over 2 months ago because we refuse to allow… [Video]. Instagram. https://www.instagram.com/p/C9OnhAnt8lD/

INSAF [@Insafuottawa]. (2024d, July 4). Occupy Tabaret Meeting Update. [Photograph]. Instagram. https://www.instagram.com/p/C9ArUKDx0N2/?hl=en&img_index=1

Siddiqui, U. (2024, April 23). In numbers: 200 days of Israel’s war on Gaza. Al-Jazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/4/23/by-the-numbers-200-days-of-israels-war-on-gaza

United Nations. (2024, April 18). UN experts deeply concerned over ‘scholasticide’ in Gaza. United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner. https://www.ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2024/04/un-experts-deeply-concerned-over-scholasticide-gaza

uOttawa [@uottawa]. (2024, April 28). Message to the uOttawa community on freedom of expression. [Photograph]. Instagram. https://www.instagram.com/p/C6U3gz0grhL/?igsh=MTR0bTd5OXpuamdxeg==

Footnotes

[i] Throughout this piece, we refer to Tabaret Hall and its lawn as “Hind’s Hall”, the “People’s University for Gaza”, “Tabaret Lawn” and the “Liberated zone”. We refer to the encampment as “Occupy Tabaret”, “camp”, and “the encampment”.

[ii] In Canada, territorial land acknowledgements have become commonplace in the last decade. We urge our readers to conceptualise territorial acknowledgments as “sites of potential disruption…[that] can be transformative acts that to some extent undo Indigenous erasure. The fact of Indigenous presence should force non-Indigenous peoples to confront their own place on these lands” (âpihtawikosisân, 2016). Canada’s nationhood was constructed on First Nations, Inuit, and Metis lands that were largely stolen by British and French settler-colonialists. There are many lands in Canada that remain unceded today, and many others whose treaty agreements have never been realised or broken. The University of Ottawa occupies the ancestral and unsurrendered territories of the Anishinaabe Algonquin. Many First Nations, Inuit, and Metis peoples and non-Indigenous peoples refer to Canada as “Turtle Island”. In this piece, we’ve intentionally replaced colonial place names wherever possible.

You may republish this article, either online and/or in print, under the Creative Commons CC BY-ND 4.0 license. We ask that you follow these simple guidelines to comply with the requirements of the license.

In short, you may not make edits beyond minor stylistic changes, and you must credit the author and note that the article was originally published on Home/Field.