By: Josh Mullenite

"In the short film that accompanies this text, I want to highlight the sights and sounds. I want viewers to not just read about the failures of infrastructure, but to bear witness. I also want to show how, within only a short distance, there exists relative serenity; how easy it might be to imagine this calm in spaces currently occupied by the highway."

When I moved into an apartment at the end of a block adjacent to the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway in Sunset Park, Brooklyn in 2018, I was going in blind. I had recently accepted a job as a Visiting Assistant Professor at Wagner College and didn’t have the time or money to apartment hunt in New York City. I found a place online, convinced the landlord to give me a video tour in the days prior to constant Zoom calls, and eventually signed the lease all from Florida, without ever having stepped foot in the borough. I knew the highway would mean air pollution, that it would mean some noise. I knew that it would not be a very good neighbor, but my options were limited. What I didn’t expect was that it would constantly shake the foundation of the townhouse in which our apartment had been carved out. I didn’t expect the thin layer of black film covering every surface if we dared leave our windows open. I didn’t expect the constant car crashes, street races, and other forms of traffic violence to be so commonplace they became part of the background noise of my life. Despite having read and written significantly on the built environment and specifically on the incursions into the daily lives of the people who live near infrastructural arteries, I could not imagine what it would be like.

That the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway and its sibling highways have been a social, political, and environmental disaster is not new information (Berman 1988, 290-312). Neither is the direct impact on a poor and mostly immigrant neighborhood as a short section of the highway rides above 3rd Avenue in Brooklyn (Caro 1975, 520-525). But a textual history and analysis of the highway doesn’t serve to highlight the dangers of the roadway or how it acts as an ever-present aspect of daily life for the thousands of people who live in its shadow. Even in detailed, long-form analyses such as Tarry Hum’s (2014) Making a Global Immigrant Neighborhood: Brooklyn’s Sunset Park, the highway only appears occasionally and as a backdrop rather than as an active participant in the lives of people who live in the area. In the short film that accompanies this text, I want to highlight the sights and sounds. I want viewers to not just read about the failures of infrastructure, but to bear witness. I also want to show how, within only a short distance, there exists relative serenity; how easy it might be to imagine this calm in spaces currently occupied by the highway. In anthropology and some parts of geography, sociology, history, psychology, and so on the idea that a researcher needs to actually be in space to understand it is so well founded that it sometimes seems taken for granted. The sights, sounds, and smells, the feeling of the air, the movement of the space are affective and evocative. But how can we translate those feelings in our research outputs? This is an experiment in creating an audiovisual backdrop that might accompany other works.

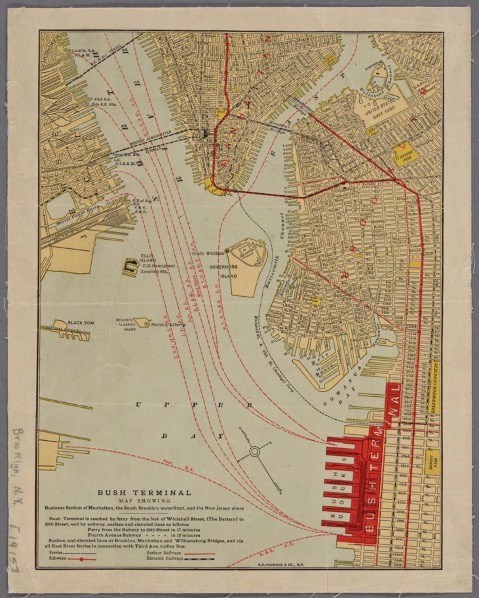

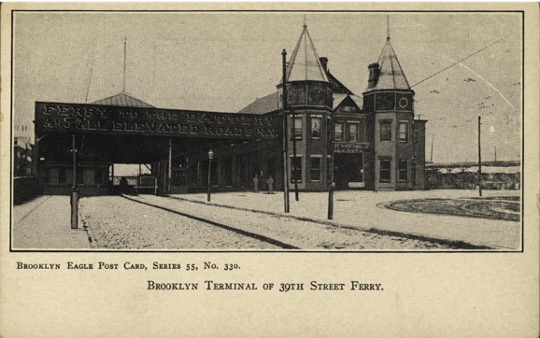

Built sometime in the 1870s or 1880s, our townhouse predated the highway by more than 60 years and would be approaching 100 years old once the construction and expansion finally stopped. It originally sat next to three larger apartment buildings, one of which had a small grocery store in its ground floor and all of which had been completely torn down to make space for the highway, leaving it with an odd lean as it had settled into its neighbors and then resettled after their demolition. When it was built, an elevated train passed by above Third Avenue, part of the Brooklyn Rapid Transit (and later, Brooklyn-Manhattan Transit) Fifth Avenue Line, which ran from 65th Street to Atlantic Avenue, making connections to a ferry terminal to Manhattan, New Jersey, and Staten Island (Figures 1-4 show some of these transit connections in action and provide a contrast to the more recent scenes in the film; all archival figures show their complete captions which may provide additional context). The ferry, which opened in 1909, brought both workers and trucks of goods to and from the nearby warehouses and factories. The ferry was closed in the 1950s after a fire at the Staten Island Ferry Terminal. Its most recent use has been as a makeshift morgue, first run by the National Guard and later as a place where bodies could be stored for indeterminate periods of time until they could be picked up and buried in mass graves in New York’s Potter’s field (film timestamp 12:23-12:48).

With the unification and later municipalization of the train system in 1940, the 5th Avenue Line was replaced with a 4th Avenue Subway Line, which not only ran deeper into Brooklyn, but which also offered further connections to the city’s transit system (Sparberg 2014). In Whiter and wealthier Park Slope, the tracks for the 5th Avenue Line were removed and today, except for a few vacant lots owned by the Metropolitan Transit Authority, there’s no way to know that a train had once run overhead.

"Portions of the film accompanying this text were shot at locations which were once living rooms, bedrooms, and sales floors. They were filmed at locations where the violence of the highway and the roadway beneath it continue to take lives."

Steel support beams were built to support the highway for most of its length, but from 65th Street, its original beginning, to 37th Street, Moses placed the highway atop the existing steel beams meant to support the railway. Figure 5 shows the abrupt transition between the two types of support beams in use. In February 1940, as plans came into clearer view, the paper reported that the “street-level truck route, under the highway [would] traverse the industrial area along the South Brooklyn Waterfront and lead to the Brooklyn outlet of the tunnel.” Seeing as 3rd Avenue was not at this time fully industrial but was primarily a shopping, entertainment, and residential corridor it seems as though at this point 2nd Avenue was still the primary option. On March 12, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported that the Third Avenue Property Owners and Merchants Association officially opposed the plan, as the highway would “blot out to a great extent light, sunshine and air from apartments and stores facing the highway.” The details of this plan and the disputes about it are ably laid out elsewhere (e.g., Caro 1975, 522). What attracted Moses to 3rd Avenue remains unclear but much of the speculation (e.g., in Caro 1975) centers around the income and immigration status of Sunset Park’s residents who were at the time primarily of Irish and Italian descent, and who were significantly poorer than residents of neighboring areas which Moses’ highway system avoided. HOLC maps show the areas where the highway being built as “D” graded, predominantly Italian and Irish, and with an annual income between $1200 and $1800, versus areas of Bay Ridge to the south which were predominantly British, with incomes ranging from $2500 to $25,000. The disparities remain today as the areas around the highway in Sunset Park are today Mexican, Puerto Rican, and to a lesser extent Palestinian, while areas of Bay Ridge away from the highway remain predominantly white.

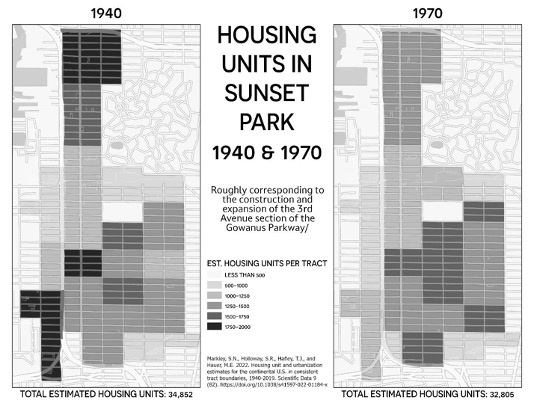

To make space for construction equipment and then later when the highway would be expanded from four lanes to six, over 400 buildings were torn down (Figure 6 shows the aftermath of this at the northern end of the highway). Sunset Park lost 2,047 housing units between 1940 and 1970, the period roughly corresponding to the initial construction (beginning in 1941) and later expansion (ending in 1964) of the highway above Third Avenue. However, in the census tracts bisected by the avenue and highway, the total number lost is 3,148, from 18,357 in 1940 to 15,209 in 1970 (Markley, et al. 2022). Figure 7 shows the geography of this housing unit loss.

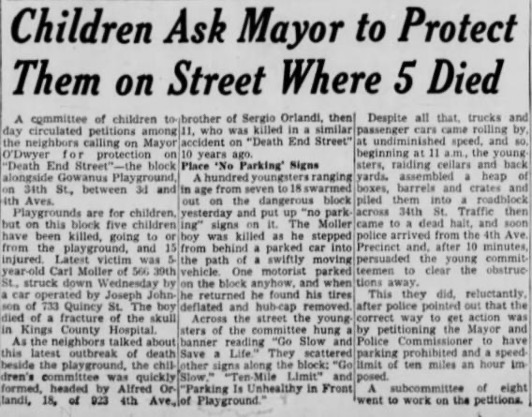

Beyond the physical destruction of housing, the changes to the neighborhood between residential 3rd Avenue and the industrial waterfront also exposed residents to new and immediate hazards. The tunnel to the city at the end of Moses’ parkway had re-started heavy industry in the area, more than could fit on ferry boats even when they were running. But because the Gowanus was a Parkway System (on which large trucks and commercial vehicles are not allowed) they would need to leave the industrial area on surface streets to connect to other parts of the city. On September 2, 1949, a “committee of children” petitioned neighbors to stop traffic on 34th Street between 3rd and 4th Avenues. The petitions were the negotiated response after the kids, spurred by the vehicular murder of 5-year-old Carl Moller, first created their own no parking signs and later barricaded the street, extending the existing playground into the street. The playground still exists, now adjacent to Sunset Park High School, but 34th Street Remains open to thru traffic (8:15-8:50, 9:41-10:12; Figure 8). On September 27, 1954, three year old James Karl of 5011 3rd Avenue, a building which would be torn down to widen the highway in the 1960s, was crushed under a coal truck at 50th Street and 2nd Avenue. Families, led by kids, blocked the street and demanded that 50th Street be closed to traffic and turned into a play area for kids (Figures 8 and 9). The street remains open and continues to act as a thoroughfare for trucks leaving more industrial First Avenue (12:49-13:41 shows 51st Street and 1st Avenue).

"It is my hope that, when we think and write about infrastructure in North America (and anywhere) we don’t see it as abstract but as a neighbor, as a part of daily life, and as something that people might already have envisioned as existing differently."

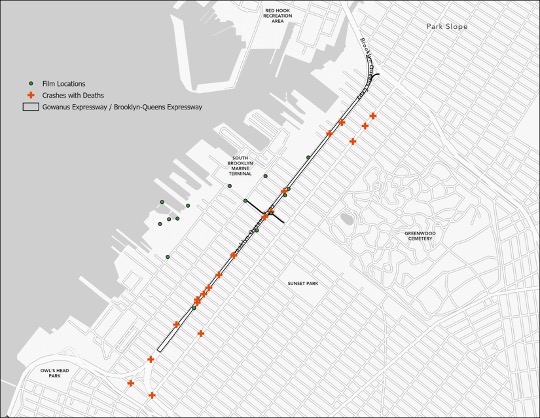

Portions of the film accompanying this text were shot at locations which were once living rooms, bedrooms, and sales floors. They were filmed at locations where the violence of the highway and the roadway beneath it continue to take lives. Filming locations are shown in Figure 10. Also in Figure 10 are the 21 crashes on, under, and within a block of the highway which have resulted in death between August 2012 and July 2022 (the extent of New York City’s public records as of October 18, 2022). This was the case on July 29, 2019, at 8:41am when an inattentive tractor trailer driver struck and killed artist Em Samolewicz in front of that playground where children had once demanded safety and whose memorial, shown in the film, has since been removed because it had been so damaged by cars hitting it. It was also the case when, on December 19, 2019, a box truck struck 85-year-old pedestrian Brendan Gill at 38th Street, an intersection also featured in the film. At the same time, in the film you can see places where both the city and private developers have been able to create spaces of serenity, at least for some, away from the rumbling of the highway as the now 140-year-old steel beams struggle to support a dying infrastructure.

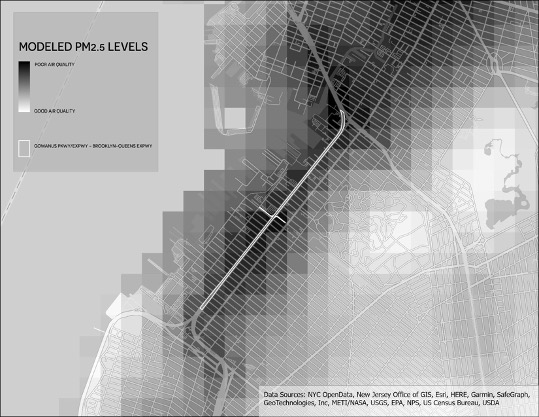

It is my hope that, when we think and write about infrastructure in North America (and anywhere) we don’t see it as abstract but as a neighbor, as a part of daily life, and as something that people might already have envisioned as existing differently. That we attend not just to its politics but also to its aesthetics, its audacity, and its existence in a multitude of forms which not only shape but also violate individual ideas of space, place, and belonging. The Brooklyn-Queens Expressway, and especially the portion made up of the former Gowanus Parkway, is a bad neighbor. The traffic brought by the highway is omnipresent both in the noise (as in the film) but also in the high levels of fine particulate matter which make their way through open windows and cracks in doors to coat every interior surface. Blocks away, in those parts of Sunset Park which have been spared by the highway, have significantly cleaner air (Figure 11). It is a neighbor that lingers on the mind, in advertising for hospitals (13:40) and in advertising enticing people to leave the city (Figure 12).

Josh Mullenite is an Assistant Professor of Anthropology and the Director of the Environmental Studies Program at Wagner College in Staten Island, New York. Their research examines the everyday impacts of past infrastructural decision-making, particularly as they relate to the creation of climate change related risk and the possibilities for future climate adaptation.

Social Media

Instagram: @josh_mullenite

Mastodon: @mullenite@fediscience.org

Further Reading

Berman, Marshall. 1988. All That Is Solid Melts into Air: The Experience of Modernity. Penguin Books.

Caro, Robert. 1975. The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York City. Vintage Books.

Connolly, N.D.B. 2014. A World More Concrete: Real Estate and the Remaking of Jim Crow South Florida. University of Chicago Press.

Hum, Terry. 2014. Making a Global Immigrant Neighborhood: Brooklyn’s Sunset Park. Temple University Press.

References Cited

Berman, Marshall. 1988. All That Is Solid Melts into Air: The Experience of Modernity. Penguin Books.

Caro, Robert. 1975. The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York City. Vintage Books.

Hum, Terry. 2014. Making a Global Immigrant Neighborhood: Brooklyn’s Sunset Park. Temple University Press.

Sparberg, Andrew J. 2014. From a Nickel to a Token: The Journal from Board of Transportation to MTA. Fordham University Press.

Markley, S.N., Holloway, S.R., Hafley, T.J. et al. 2022. Housing unit and urbanization estimates for the continental U.S. in consistent tract boundaries, 1940–2019. Scientific Data 9:82. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-022-01184-x

You may republish this article, either online and/or in print, under the Creative Commons CC BY-ND 4.0 license. We ask that you follow these simple guidelines to comply with the requirements of the license.

In short, you may not make edits beyond minor stylistic changes, and you must credit the author and note that the article was originally published on Home/Field.